FULL OF IT

Hasty but Fond Notes on Bob Huot’s Diary Paintings

Whooo-eee! Bob Huot’s Diary Paintings! They demanded the kind of involvement from a viewer that went into them from the painter. Hollis Frampton called them “gifts, freely given…made with love…a fundamentally sociable activity.” Which is interesting, because for all their privacy (only Huot can decipher the specifics), they are highly communicative works of art. What they leave out, or reject, is the privacy of style – that incestuous elitism of art only about art that makes so much painting unavailable to a general audience and just plain uninteresting to a specialized one. In these scrolls, which unroll across floor, wall, space and time, Huot can do anything he wants. How many artists can say that?

In the mid-60’s Huot was one of the better “minimal” painters, usually working in color but occasionally rejecting that too, as beautiful canvases consisting of no canvas, but a knobby-surfaced transparent nylon over a stretcher visible beneath. Then came the tape pieces and the glow-tape pieces, focusing real spaces, and shadow pieces cast by existing fixtures or objects, and a show that was a room with floors sanded and polyurethaned and two walls painted a deep Pratt and Lambert blue; then still more invisible work – exhibited anonymously, in the case of the MOMA Information show (a ladder, quickly removed from the premises by a curator), or exhibited under his name referring out into the world to a different hand-painted “found painting” in the city every day (for a Whitney Annual), or, in my book Six Years, the anonymous story of the Great Griswald’s artistic ambitions.

After he stopped painting, Huot seemed to say fuck distillation and style and began to intervene in life, though the process of rejection was necessary so that the process of acceptance could begin – a cycle similar to the one the art world periodically undergoes. Politics had a lot to do with it. The kind of awareness that went into the Diary Paintings doesn’t come strictly from navel-watching. The cycles are those of a living organism too. Down on the farm or in the city, Huot watched nature and people grow, get cut down, grow again. A committed communicator, he was one of the first to recognize the implications of art world politics and their connection to world politics. (In 1968 he wrote to me about an anti-war benefit show we were co-organizing, “well – maybe just making something is anti-war.”) Huot’s retreat to a farm in upstate New York, around the time of Kent State, Jackson State, and the bombing of Cambodia, represented a disgust with the world and the way art was being used as well as a personal decision. He was active at the time in the Art Workers Coalition. The diary films, which began when he went to the country, were clearly a personal necessity at the time – a deeply felt need (then shared by many of us, though few acted upon it) to re-integrate one’s life and one’s art.

Huot had been making films since 1966 from scraps of found footage, then bought his own Bolex in 1970. For a while film seemed the way to “get out of art.” But by May 1971, he was missing painting, the making of things, the artist’s addiction. (“I really like to paint. It’s a nice thing to do.”) He had a lot of leftover canvas in long rolls and started “trying a little something every day, as arbitrary and thoughtless as possible.” What ever happened, happened. Different days, different materials – creosote, magic markers, oil, plastic sheets, black cloth – and different matters – violent, contemplative, cries of pain, cries of joy, day by day, “trying to open it up for myself.” Diary #9 from January 1972 is called “Random Gestures” . Despite the written entries, some of them from bad times and not hiding it, not ashamed to cry, the paintings “didn’t start out to be autobiographical in the literal sense.” They are art, feelings recorded in “color, texture, in the tradition of painting.” But they are art full of life, the kind of life artists aren’t accustomed to welcome into art. They go from personal to communicative, skipping over the analytical, the middle ground where the specialists play.

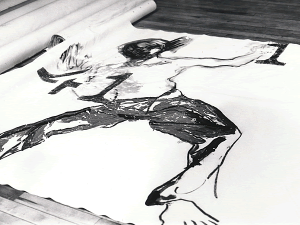

It was soon clear to Huot that the paintings were not diaries in the sense the films were. In fact they reverse the films. Where one shows people, places, animals, work, events, the other scratches the surface and disappears into it. The paintings come from where good paintings always come – inside. But Huot’s isolation (in the country, in academe, away from the commercial art world) freed him from pressures which might have engendered a far more self-conscious kind of narrative or autobiographical art. The scrolls are not “conceptual”; they are big, brawling, unfolding surfaces of paper or canvas – fields or arenas of experience and play. No holds are barred. Anything goes. “Advance” vanishes and the artist is suddenly “permitted” to be old hat, new hat, corny, sentimental, brutal, ecstatic, up, down, all the hell over the place. Styleless in their components, their style is that amalgam.

The Diary Paintings are very realistic, like people’s lives. The structure is loose, moment to moment in most of them, though others are more controlled and esthetically oriented. The only restrictions are internal. If they are sometimes, almost in spite of themselves, very beautiful that’s because that happens sometimes. It makes for happiness. My favorite ones are the heavy ones, with great weights floating and plunging across and into the ground, and those with layers of words crisscrossing the shapes, where emotion bursts out in another medium. I love their ease, their rhythms. The whole idea of unrolling is full of drama, suspense. What is the next day going to bring? They are obviously fun to make and that comes across till I identify with the making, vicariously enjoy some of that felt activity, relive with my own vocabulary the events laid down in Huot’s.

The first nine scrolls were made relatively sequentially, like frames of movies though different personae seem to take over different surfaces, some more “serious”, some more desperate than others. The 10th scroll – very large, frankly disjointed, crazy, awkward, in the American tradition – includes “entries” by his baby son Jesse in December 1972, and also some very handsome painterly drawings of nudes, sensuous in the best sense, enjoyable by both subject and object. Resolutely retrograde, they would be trite if framed, if small, but in the context of the scroll they are something else, not rather Picassiod illustration, but a means of activating the other components in their difference with “high art” and in the sheer luscious luxury of such an indulgence. One nude is partially overlaid with a transparent rectangle of varnish – a “quote” from Léger. In fact, an art historian could have a fine time with these patently unhistorical paintings. There’s a lovely parody of Still, a phrase from de Kooning, a corner of a Picasso painting…The new works are not diaries any more, but within a similarly free framework they focus on specific themes or ideas. “The Players”, part abstract, part realistic, is about political cartoons.

Huot would like to see scrolls scrawling across public spaces, like schools, maybe the subways, even the streets, so that they can stay alive. They are actually like graffiti, with the kind of vitality that comes from real spontaneity, combined with the eye of a professional painter who has managed to free himself from tight-ass formal considerations but retains an innate knowledge of how things look/feel. As in the case of the young graffiti writers whose subway and street work is terrific and whose “art” shown in galleries is dead, the excitement of the execution in risky (physical or psychological) circumstance is very much part of the impact. I don’t think I feel the Diary Paintings so strongly just because much of my experience has been like Huot’s, or because we’ve picketed, danced, argued, and cried together. Sincere outward-bound energy is rare, I hope the scrolls get out into the world further and further so non-art audiences can enjoy what happens when a real artist goes public.

Lucy Lippard

Lucy Lippard has been a free-lance critic for the past ten years, a feminist, and the author of seven books on contemporary art, with more to appear shortly: “Eva Hesse” and “Essays on Woman Artists.”